The Soil of Liberty

If interested in listening to a discussion about the article please click below

The Bassett Settlement and the Black Agrarian Dream

In the quiet swales of Ervin Township, Indiana, along a road once printed on maps with a racial slur, there lies a small, uneven patch of ground that refuses to disappear. The Bassett Cemetery is easy to overlook. Most of its markers have surrendered to weather and neglect, their names dissolving back into the soil. Yet this is not merely a burial ground. It is the last visible trace of a Black republic built with plows, prayer, and property deeds, a community that understood land, not law, as the surest guarantor of freedom.

One surviving headstone belongs to Zachariah Bassett. Its inscription reads like a whispered sermon across generations: “Remember friends as you pass by, As you are now so once was I; As I am now so you must be, Prepare for death and follow me.” The words are less a warning than a reminder. This soil remembers.

“Remember friends as you pass by, As you are now so once was I; As I am now so you must be, Prepare for death and follow me.”

Long before the Great Migration drew Black families from southern farms into northern factories, the Bassetts and their kin undertook a quieter exodus. Theirs was not a flight toward wages or industry, but toward acreage. They believed freedom could not be sustained on employment alone. It had to be owned.

The story begins in eastern North Carolina at the end of the eighteenth century. Britton Bassett was born free in a slave society, an exception so fragile it bordered on illusion. His status rested on his white mother, under a legal doctrine that tethered a child’s fate to maternal lineage. When he came of age, Bassett received manumission papers, a horse, and a modest sum of money. It was not wealth, but it was possibility.

By the 1830s, that possibility was narrowing. In the wake of Nat Turner’s rebellion, southern legislatures tightened their grip on free Black people. Voting rights disappeared. Movement was curtailed. Special taxes were imposed simply for remaining free. Worse were the kidnappers, men who hunted free Blacks and sold them south with forged documents and official indifference.

The Bassetts did not wait to be caught in the vise. They moved.

Their journey north was careful and deliberate. Travel by night. Hide by day. Cross the Ohio River, the symbolic threshold between bondage and uncertain promise. In Indiana, they first settled among Quakers, whose opposition to slavery extended beyond moral protest into schools, shelter, and land access. Literacy followed quickly. Education was not ornamentation; it was defense.

By the mid-1850s, the Bassetts and several allied families relocated again, this time to Howard County. They did not arrive as laborers seeking work. They came as buyers. The land they acquired lay within the so-called Seven Mile Strip, former canal lands resold by the state. Here, Black families did something quietly radical: they purchased property outright and built an autonomous rural economy.

The settlement that emerged was modest but complete. There was a store, a post office, a schoolhouse, a blacksmith. Fields produced food not only for survival, but for sale. By 1870, members of the community held real estate valued in the thousands of dollars, wealth that rivaled or exceeded that of many white neighbors.

At the center stood the Free Union Baptist Church. It was not merely a place of worship. It functioned as parliament, courthouse, and moral compass. Sermons doubled as civic instruction. Faith and governance were inseparable. Leadership was not symbolic; it was exercised.

Zachariah and Richard Bassett preached from the pulpit and organized from the ground. A schoolhouse ensured that children were literate, disciplined, and prepared for a nation that would not welcome them easily. This was a community that treated freedom as a daily practice, not a legal abstraction.

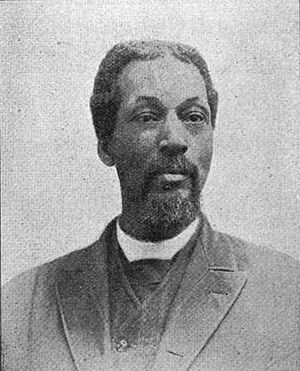

That discipline eventually carried one of their own into state power. In 1892, Richard Bassett was elected to the Indiana House of Representatives, one of the few Black men to reach the General Assembly in the nineteenth century, and rarer still, elected by a largely white constituency. His politics reflected the settlement’s values. When presented with a proposal to open the World’s Fair on Sundays, Bassett voted no. Commercial spectacle would not override Sabbath principle. He did not bend.

The family’s claim on citizenship extended beyond ballots. It extended to blood. Effie Bassett served as a Buffalo Soldier during the Spanish-American War, enlisted in a segregated regiment built on racist myths about Black bodies. He died of yellow fever in Cuba. His family fought for years to bring his remains home. When they succeeded, he was buried with honor. Even in death, the Bassetts insisted on dignity.

The settlement did not fail. It dispersed.

By the late nineteenth century, natural gas transformed nearby Kokomo into an industrial magnet. Factories rose. Wages beckoned. The younger generation, educated, mobile, unafraid, left the fields for furnaces and glassworks. By 1920, the Bassett Settlement no longer functioned as a cohesive rural community. Its success had rendered it unnecessary.

Yet the lineage endured. Pearl Bassett, born in 1909, lived more than a century. She became a civil-rights organizer, helping establish local chapters of the NAACP and the Urban League. She carried the agrarian discipline of her ancestors into urban activism, bridging eras without abandoning principle.

The Bassett Settlement complicates a familiar story. It challenges the notion that Black life in the nineteenth century was defined solely by dispossession and protest. These were people who anticipated exclusion and responded with infrastructure. Who met terror with titles to land. Who understood that freedom without ownership was temporary.

Today, the offensive road name has been changed. Progress, of a sort. But the cemetery remains, quiet, instructive, unfinished. The stones that endure remind us that Indiana soil once sustained a Black agrarian dream: one rooted in self-rule, moral authority, and the stubborn belief that liberty must be cultivated, season after season, by one’s own hands.

Sources & Further Reading

Howard County, Indiana: A Pictorial History, Howard County Historical Society

https://howardcountyhistory.orgUnited States Federal Census Records (1850–1900), Howard County, Indiana

https://www.archives.gov/research/censusIndiana General Assembly Historical Records

https://www.in.gov/library/collections-and-services/indiana-collection/indiana-general-assembly-documents/Howard County Deed & Land Records (Seven Mile Strip / Canal Lands)

https://www.in.gov/counties/howard/recorder/Free Union Baptist Church (Howard County) – Historical Reference

https://www.in.gov/dnr/historic-preservation/U.S. Army Military Service Records – Spanish-American War / Buffalo Soldiers

https://www.archives.gov/research/military/army/spanish-american-warIndiana African American Heritage Initiative

https://www.in.gov/dnr/historic-preservation/african-american-heritage/Oral histories and family records of the Bassett, Artis, and Ellis families

(Privately held; excerpts referenced with permission)